The Philly Budget 101

A special primer on the eve of budget day

Good afternoon loyal readers. In advance of tomorrow’s budget address, I wanted to share a budget explainer I wrote in partnership with the Committee of Seventy for its “How Philly Works” guide. If you haven’t yet gotten a chance to read it, please check it out and share. It’s an incredible resource for residents wanting to learn more about how their government operates, or who are interested in becoming a more engaged citizen.

Today, I’m highlighting the section of the guide on the City budget to help you get a better understanding of the budget process and how our tax dollars are allocated and spent. For tweet by tweet coverage of tomorrow’s Mayoral budget address and Council’s stated meeting, follow me on Twitter @broadandmarket. And if you haven’t yet, please subscribe to ensure same day delivery of City Hall Roll Call to your inbox.

The City Budget 101

Under state law, the City of Philadelphia must pass a balanced budget. Unlike the federal government, the City cannot plan to spend more money than is estimated will be collected in tax revenue. Philadelphia’s fiscal year runs from July 1st through June 30th. The June 30th deadline is a hard deadline for budget passage, as the City is not permitted to change tax rates in the middle of a fiscal year.

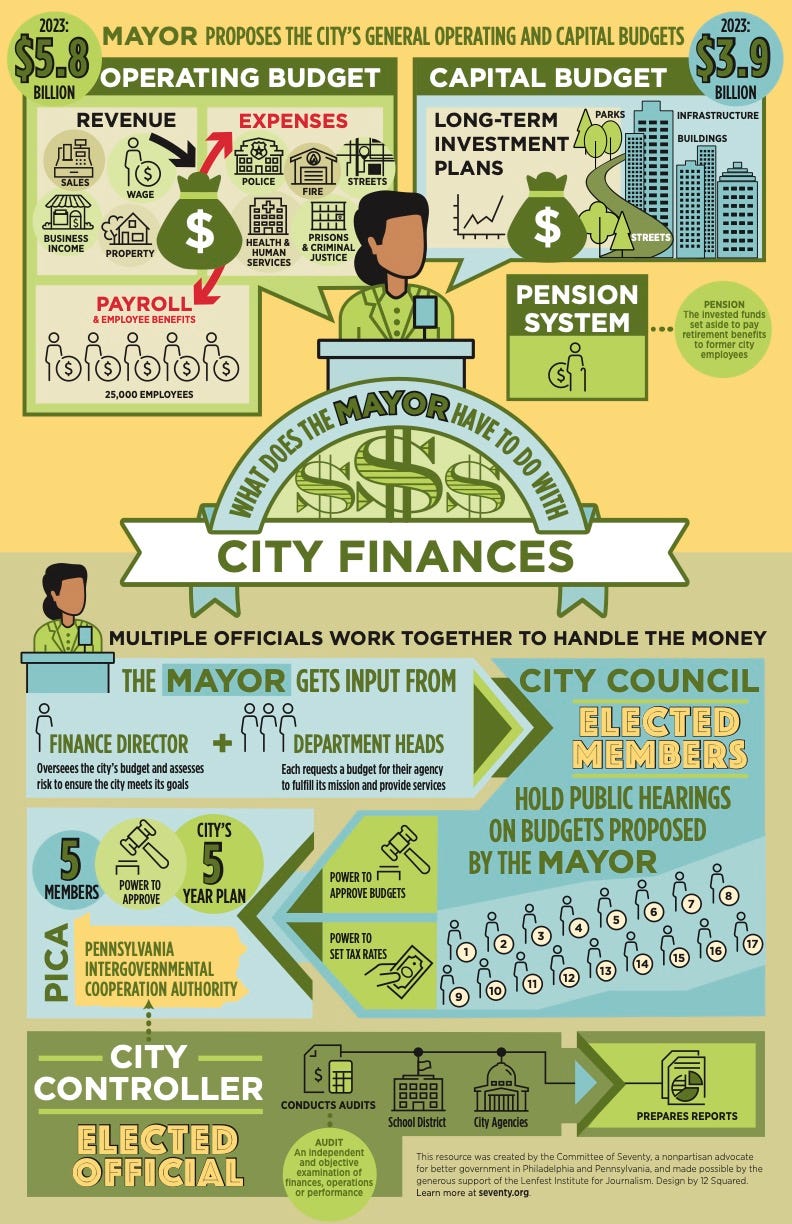

Both the Mayor and City Council have important roles in the budgetary process. No later than 90 days before the end of the fiscal year, the Mayor must send City Council a proposed annual budget for the upcoming year. This year’s budget presentation is scheduled for tomorrow, March 14th. At this time, the Mayor will give a budget address to Council that acts as the City’s “State of the Union,” with representatives from the major operating departments present in Council Chambers to hear the Mayor outline their vision for the next year.

While the budget address is usually delivered in March, the actual budget process starts well before that. The City’s budget director works closely with leaders across the various departments and offices to anticipate the amount of resources needed to carry out the agency’s mission. Additionally, the Revenue Department closely monitors economic and tax collection trends to predict how much the City should expect to collect from taxpayers.

City Council’s Budget Role

Following the Mayor’s budget address and the introduction of the necessary legislation by a member, Council will hold a series of public hearings on the proposed budget. The budget hearings are held before the Committee of the Whole, made up of all seventeen Councilmembers. Unlike other council hearings, which provide an opportunity for the public to speak, most budget hearings do not feature public testimony. Rather, each hearing is dedicated to a specific topic or department.

Budget hearings are an opportunity for Councilmembers to engage directly with department leaders, ask questions about programming and operational decisions and get updates about the effectiveness or status of ongoing projects. Every major department and agency funded through the City budget is included in the hearing process, save one—City Council itself, despite an annual budget of around $18 million.

The final hearing days are typically reserved for the public to comment on the city’s budget. But while the public-facing process unfolds, there is a lot of negotiation going on behind the scenes. Many Councilmembers negotiate directly with the Mayor around their own priorities. In recent years, Council-driven negotiations have led to additional resources for gun violence prevention programming, library resources and commercial corridor cleanup, above the increases originally proposed by the Mayor. It is incredibly difficult to track these individual negotiations, which are all captured in a final omnibus amendment to the budget bills.

A number of budget bills will be introduced at tomorrow’s session. These include the City’s operating budget, the capital budget and the Five-Year Plan. First up is the operating budget which constitutes the majority of the city’s spending plan.

The City Operating Budget

Money In

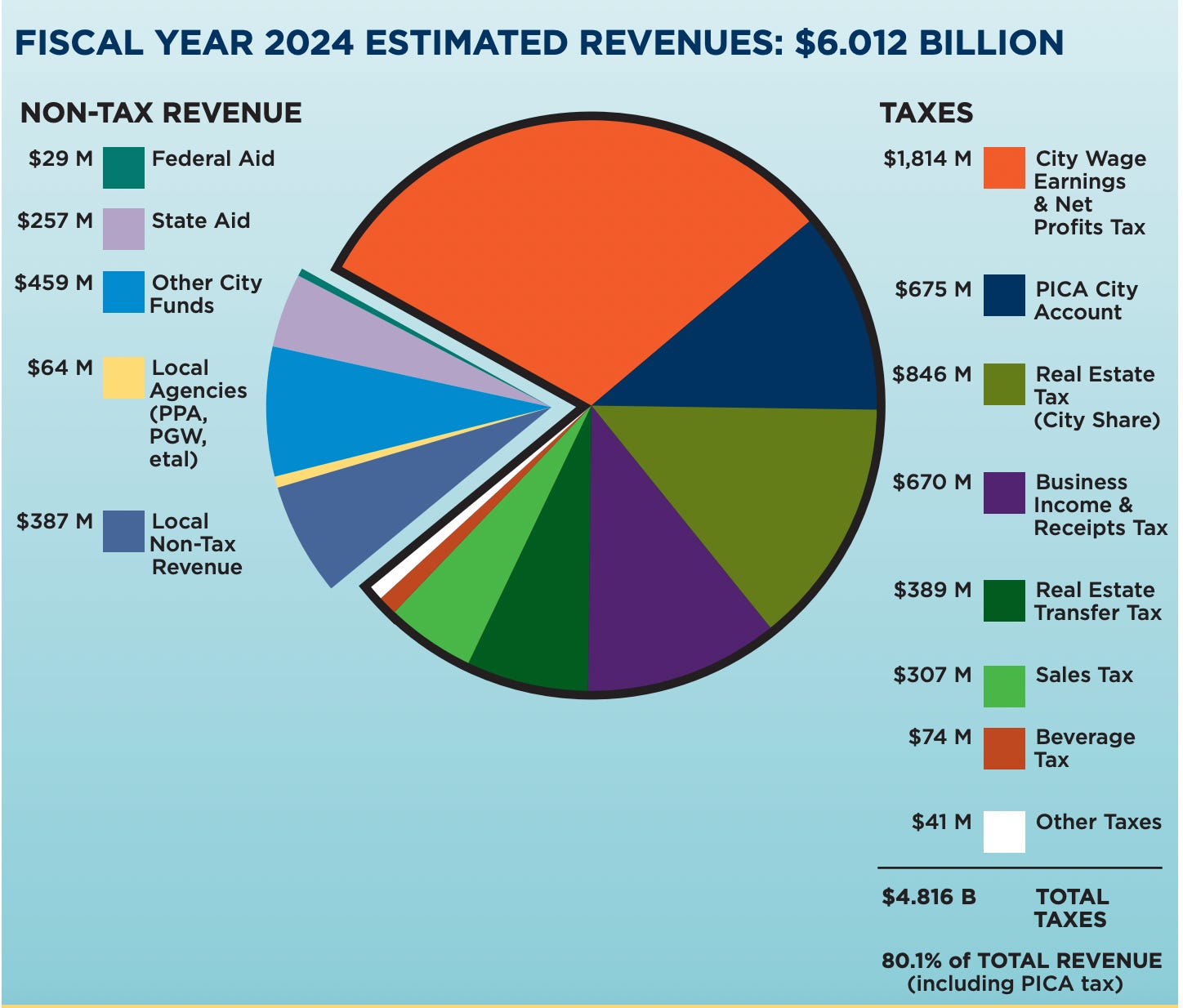

Last year’s operating budget included approximately $6 billion in spending. The budget supports core municipal functions like policing and law enforcement, firefighting, trash collection, parks and libraries, as well as the internal costs of running the city (e.g., fleet management, legal services, equipment and materials). Most of this spending is funded through taxpayer dollars.

The three biggest sources of tax revenue are:

The City Wage Tax, which is paid by Philadelphians and non-Philadelphia residents working in the City. The Wage Tax accounts for approximately 29% of the City’s tax revenue—over $1.7 billion dollars annually.

The Real Estate Tax, which generates approximately $800 million a year, or 14% of the City’s revenue. Fifty-five percent of these funds go to the School District of Philadelphia.

The Business Income and Receipts Tax, which brings the city around $700 million annually, or ~12%. This is a tax on both the profits and revenue of businesses operating in Philadelphia.

City Council sets these tax rates in law, but the revenue generated can vary, sometimes dramatically, depending on the economy.

Money Out

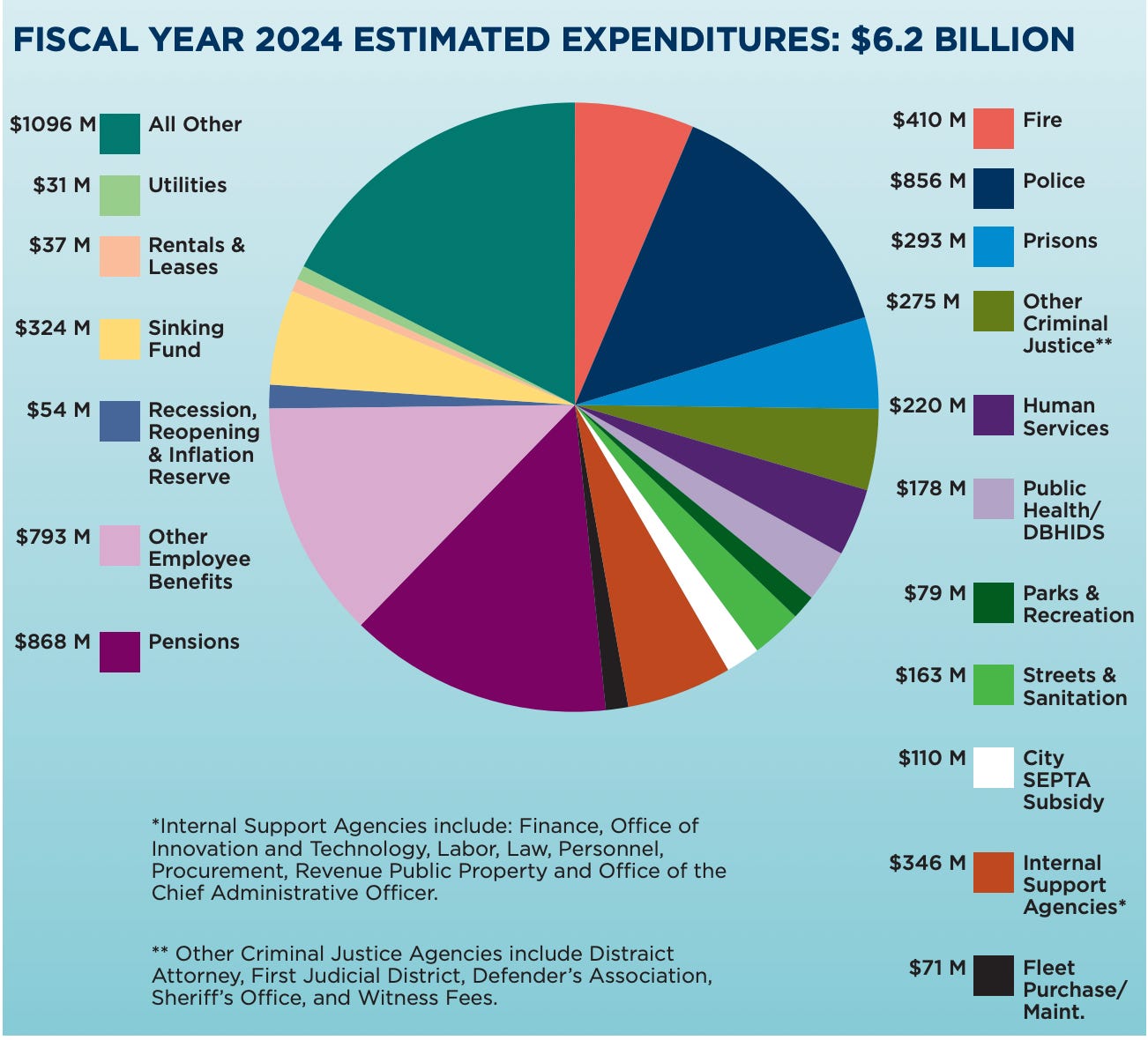

Every allocation in the City budget can be put in one of 7 main buckets of spending. Some of these buckets are “discretionary,” meaning the City can choose how much to allocate. Other buckets are “non-discretionary” meaning the City has a legal obligation to fully fund that resource. For example, the City is legally required to put a certain amount of money into the employee pension fund, which makes up a significant portion of overall expenses. On the other hand, funding for many of the city’s operating departments like Parks and Recreation is discretionary; the City can allocate as much or as little resources as it chooses.

Another important thing to understand is that there are two main revenue collection accounts for City spending. First, the general fund is the main account used by the City to collect the various tax and revenue streams. The second is the grants fund, through which federal, state and local grants flow.

Spending Buckets

Bucket 1: Public Safety

The City spends approximately 30% of general revenue funds on the various departments responsible for public safety in the City. This includes Police, Fire, Prisons, and Court System (local courts, District Attorney and Public Defender). The funding to these agencies is a mix of discretionary and non-discretionary spending.

Bucket 2: Pension and Benefits

While much of City spending goes to pay the salaries of current employees, a significant chunk of its expenditures goes toward the pension obligations of retired employees. Approximately 30% of general revenue funds is paid towards Pension and Benefit obligations. This spending is non-discretionary as it includes the City’s mandatory annual payment to the Pension Fund and the cost of the collectively bargained fringe benefits for City employees, such as health and medical insurance.

Bucket 3: Government Administration

The administrative cost of running the City includes such things as offices, IT services, leases, building management and fleet management. The city spends around 14% of revenue funds on these items.

Bucket 4: City Services and Economic Development

While most residents’ regular interaction with city services revolves around trash pick-up, parks and recreation or a trip to their neighborhood library, the funding of these services constitutes only around 9% of revenue spending. The Streets Department, which is responsible both for sanitation services and street repair throughout the city, only makes up around 4% of the total City budget. Parks and Recreation and the entire library system make up only slightly over 2% of the total budget.

Bucket 5: Education

The City’s contribution to the School District of Philadelphia, funding for Pre-K and Community Schools and support for the Community College of Philadelphia makes up around 7% of the City budget. The City’s contribution to the School District must be maintained, and so while the City could choose to contribute more, it cannot reduce the amount of the contribution over time. The School District receives a significant portion of its funding through the state with a total budget of around $4.3 billion.

Bucket 6: Health and Human Services

The City spends around 7% of its general fund revenue on providing health and human service support. Like the School District of Philadelphia, the city’s contribution is only a small part of the total amount spent by the city on these services. The majority of funding in this bucket comes from state and federal grants, which are not included in the general fund, but rather the grants fund.

Bucket 7: Debt Service

The City doesn’t just run on money it collects from taxpayers. Rather, it borrows money through the sale of municipal bonds. This money funds long term capital improvements to city infrastructure. Around 6% of the City budget goes to service this debt - essentially interest payments to bondholders. This spending is nondiscretionary,

Other Budget Documents

In addition to the Operating Budget, which we discussed above, there are two other budget documents you should be familiar with: the Capital Budget and the Five-Year Plan.

The Capital Budget funds major improvements to city facilities and infrastructure. Money to pay staffers at a recreation center is allocated from the Operating Budget; money to pay for a new roof at the recreation center is allocated from the Capital Budget. Money for the Capital Budget typically comes from long-term borrowing through the issuance of municipal bonds. This type of borrowing and long-term debt must be approved by voters through ballot questions.

The Five-Year Plan is exactly what it sounds like — a five-year outlook on the city’s fiscal plan. In 1991, the City of Philadelphia was in the midst of a severe financial crisis and went to the Commonwealth for assistance. In exchange for providing the City with financial assistance, the Commonwealth created the Pennsylvania Intergovernmental Cooperation Authority (PICA) to oversee the City’s financial planning and budget processes. As part of its annual budget process, the City is required to present its Five-Year Plan to the PICA board for approval to ensure that its revenue projections and spending plan are reasonable and will result in a balanced budget.

The Public’s Role in the Budget Process

One of the most frequent questions from residents is how they can have a bigger influence on the City’s budget. There are a few ways to effectively advocate for more resources in your community. One way would be to reach out directly to your City Councilmember and let them know about the importance of the issue to you as their constituent. You could also sign-up to testify at a public budget hearing and provide your feedback to the Councilmembers.

However, as the saying goes, there is strength in numbers. Before you set out on your own, check to see if there is a group that has already organized around that issue. Whether it’s park access or library funding, after-school resources or literacy programs, there is usually a non-profit or friends group organized around a particular issue. Not only does working with a group give you strength in numbers, many of these groups coordinate campaigns and activities for their members specifically around the budget process.

FY2024-2025 Budget

Mayor Cherelle Parker will deliver her first budget address tomorrow at 10 a.m. You can watch live on Channel 64 or stream through PHLCouncil.com. City Hall Roll Call will return tomorrow with dedicated coverage to the Mayor’s budget.